By Joel Mann.

(Joel is teaching a workshop July 14, Finding your Float, at Just B Yoga)

Developing my float has been an inward journey paralleling my asana practice.

It started on the outside with an exploration of what my body can do physically. I learned that my pelvic floor not only engages, but stabilizes my torso and keeps it from toppling over. I came to understand that my breath is the physical link between stability and pliability. I began to appreciate that the quality of my breath directly reflects the attitude I bring to my mat, and likewise the intention for practice I bring to my mat will shape the quality of my breath.

Eventually my yoga stayed with me after I rolled up my mat and even after I had released my deep Ujjayi breath. I could find it at the gas station, the dinner table, and at work. I realized that just like any relationship takes effort and consideration, so too does the relationship to oneself.

I began to explore yoga just as I was beginning my career as an Occupational Therapist working in sub-acute rehabilitation with older adults. My prior yoga experience was limited to a semester-long undergraduate class five years previous.

I remember working with my first patient with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), and observing how labored each breath was while we worked in the treatment gym. Each inhalation seemed an unsatisfactory struggle, each exhale interrupted by an abrupt gasp for stuffy air. When my yoga instructor emphasized bringing an intention to each breath, softening the breath to the lowest piece of the belly, I tried the same imagery with my patient: imagine you are savoring the length of your inhale as you welcome the deep scent of a summer rose; imagine wanting every drop of your exhale to help get that wish as you carefully extinguish each candle on your birthday cake. I learned that even a skeptical patient has the capacity to appreciate the effect of one’s mental disposition on the perception of pleasure and pain, satisfaction and disappointment, ease and effort.

I remember when I first heard the term vinyasa I pictured a shallow stream with a steady current. I imagined water flowing around rocks in the riverbed without acknowledging the resistance the hard shapes offered. As we connect breath with movement in the practice of asana, we allow the breath to flow despite the physical demands of the asanas.

A gruesome callisthenic workout routine can suddenly transform into a single point of focus for the mind when we link the breath to movement. When the body yearns to gasp for its fuel we can choose to give it all the oxygen it desires through a steady and loving respiratory cycle. Rather than hastily groping for sustenance we can choose to calmly provide each serving. The mind that was once clouded with preoccupation is now earnestly occupied in the physical demands of the present vinyasa.

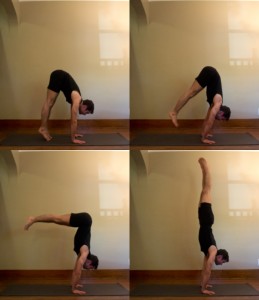

I remember first trying to jump forward from downward facing dog. I trusted that there was a reason why I should try. I kicked myself in the forearm and hurt my wrist. I kneed myself in the chin, and several times I jumped with such ferocity that I ended up diving face first towards my mat. But most of the time I bunny hopped safely into place. At first this tactic was helpful during really fast and flowing classes because at least I could save time on getting up to the top of my mat for the next sun salute (and if I got there fast enough I might be able to draw out the inhalation to my half-flat back and finally get some air!).

Eventually, with the help of Hilaire Lockwood, I learned to control my float up by first learning to jump back, by trusting the weight in my hands and learning to resist the floor and control the shifting of my center of gravity over my planted hands. Misty Flahie presented an amazing workshop on floating in 2011 where I learned that synching my breath to the jump was just as important as conscious engagement of the bandhas.

Embarrassingly, what really helped me make sense of what I was trying to do was watching David Swenson float effortlessly over and over again on his Ashtanga Primary Series DVD. I made dinner guests watch it. I made my mom watch it on her television. And then eventually, disregarding where and with whom I was watching it, I began to practice my own float.

Pattabhi Jois conveyed the importance of being on one’s mat when he described it as 99% practice and 1% theory. I could hear explanations and descriptions repeatedly, but my body needed to experience it to comprehend what it was that my instructors were instructing. Mula bandha is not theoretical—it’s practical!

As an instructor I see many students who are afraid to try to float, and even more students who will try only if directly instructed and encouraged to try. In reality the yoga studio is the safest and most convenient space for trying new things with your asana practice. Many students, and even instructors, overlook that floating serves a purpose in the grand scheme of a vinyasa-style practice. While each asana energetically connects the body in certain ways, our practice is composed of just as many transitional pieces between asanas. As yogis we can honor these transitions in a number of ways: being mindful of where we place the hands and feet, lengthening the inhalation or exhalation for the entirety of the transition, and detaching from the concept that if our body doesn’t understand what our mind is asking that we’ve done something wrong. Floating as a means of transition saves time and energy between the asanas, it presents a new edge of challenge for the yogi as well as a source for single pointed concentration, and not to mention defiance of gravity is incredibly liberating.

But if I am truly present and listening to each breath maybe I don’t float. Maybe I just sit still with the room and practice releasing the ceaseless conversation in my head. The beauty of yoga is that it offers so many tools to help us broaden our ears to listen beyond the clutter and to the true here and now.

When we practice asana it is practice for the sake of itself—there’s no dress rehearsal and thankfully no opening act. I hope that if for nothing else my workshop helps develop students’ mindfulness towards those transitional pieces of practice, and better appreciate asana practice as another tool to help us find our presence.